This blog post is part of a six-part series about supporting children’s Positive Technological Development through hybrid/distanced learning.

Full Story

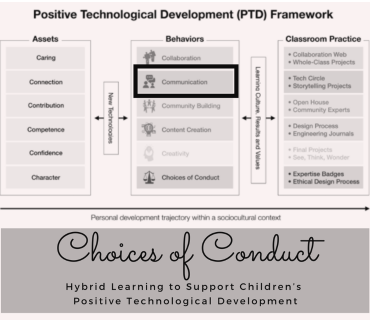

In our first post in the series, Introduction, we shared our background in education, our commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion, and a summary of foundational research in creating a learning experience for young children that aligns with Positive Technological Development framework. In this post, we are going to break down the PTD behavior, Choices of Conduct. We have invited our friend and colleague, Dr, Ziva Hassenfeld, to share a research project titled The Development of Virtues in Early Childhood Education Through Robotics.

Choices of Conduct

How can technology help children build character?

Dr. Marina Bers describes in her research how the process of making choices and observing their consequences is a character-building experience for children (Bers 2020). Character relates to a person’s sense of moral purpose and responsibility, and just like cognitive skills, character building is a believed to be a developmental process strongly informed by children’s lived experiences (Hardy & Carlo, 2011; Duska & Whelan, 1975).

The individual choices that children make when learning to use technology can impact themselves and their peers in different ways.

-

Should they play with the tablet gently, or drop it on the floor?

-

What would happen if they stole a friend’s idea for their own coding project?

-

What if instead they complimented their friend’s idea and asked for help?

The results of these actions inform the child’s relationship to their classmates, their technological tool, and even themselves. We often hear teachers lament that certain technologies provide children too much freedom, or should have certain features removed to focus children’s attention. However, by removing children’s opportunity for choices, we also remove opportunities for them to explore positive and negative consequences of their conduct from an early age. Instead, try offering technologies that are recommended and designed for children in your age group, to ensure kids can practice self-regulation, but avoid frustrating or confusing experiences with technology.

After children have become fluent in a technology (sometimes even exceeding the teacher’s knowledge), they have the power to use their new skills in helpful or harmful ways for their community. For example, children may be curious and motivated enough to disrupt the lesson plan by ignoring the teacher’s instructions to open a learning software, and instead choose to play a computer game. However, just because they can use the technology in that way doesn’t mean they should.

Learning early about the responsibility that comes with their technological skills is important preparation for future tech-literate citizens. If you want an example of the importance of conduct choices in tech, you need to look no further than current events about hackers, digital crime, and online privacy and security.

Research on PTD and Choices of Conduct

How can we use technology to have the same kinds of character-building experiences as in the classroom?

How can we use technology to have the same kinds of character-building experiences as in the classroom?While at Tufts University Angie contributed to The Development of Virtues in Early Childhood Education Through Robotics as a researcher partnered with Eliot Pearson Children’s School. “Introducing robotics in early childhood can make technology and engineering education more engaging and hands-on. But can a robotics curriculum that’s designed to be developmentally appropriate for young children also help them become better citizens and human beings?” Read more about this project in Angie’s CSTA blog post Fostering Creativity, Curiosity, and Generosity Through Robotics.

The project was conducted in four schools in the Boston, MA area and four schools in Buenos Aires, Argentina with the use of the curriculum and the KIBO robot from Kinderlab robotics. Each school was picked due to their religious and cultural focus and teachers were encouraged to modify lessons to integrate their values based on the curriculum Our Treasure: A KIBO Coding Curriculum for Emergent Readers based on a Book. You can read more in this post about the Templeton Virtues research in this month’s guest contribution from Dr. Ziva Hassenfeld below.

As you think about more ways to foster opportunities for children to practice choices of conduct at home or school, consider the following question prompts from the PTD card deck (a tool created by Dr. Bers to help educators align their technology teaching with PTD).” Watch this video to learn more about the project. Visit this page to view the curriculum used in both Spanish and English.

PTD Cards for Choices of Conduct

Design Prompts for Learning environments:

-

How does the learning environment support children in making their own learning choices?

-

How do children show respect to the space, tools, materials, and each other?

-

What are the consequences when children fail to choose positive behaviors in the environment?

-

How do children show respect to each other?

-

In what ways do facilitators engage children in respectful conversations about choices?

Design Prompts for Technologies:

-

How can children make their own decisions regarding how they use the technology?

-

How can children take risks when using the technology?

-

In what ways does the technology require that children handle it with care?

Choices of Conduct in Context

Why is it important to support children in making their own choices of conduct? How do we develop appropriate consequences for helpful and harmful conduct?

When thinking about choices of conduct, it’s helpful to remember two important lessons from the field of Positive Psychology about how to change behavior patterns:

-

Negative punishment for negative behaviors – bad things happen if you make a harmful choice

-

Positive reinforcement for positive behaviors – good things happen if you make a helpful choice.

Often it’s easy to slip into the habit of administering a punishment (like staying inside during recess) as a consequence for negative behavior. This can backfire, leaving children frustrated and confused about why they are being punished. A simpler tactic is to simply remove the reward, which links the consequence directly to the unwanted behavior.

For example, Ms. Jones’ Kindergarten class is learning about butterflies. Students were asked to create a picture of the lifecycle of a butterfly and submit it to Seesaw. Ethan chose to submit an inappropriate picture instead of his butterfly project. Instead of punishing him by taking away his computer time next week, Ms. Jones simply did not post Ethan’s submission publicly on Seesaw. She tells him privately that she is sorry his work will not be shared this week, but he can try again next week by choosing to submit his project correctly, and then he will be invited back to present. Instead of wasting valuable class time and teacher energy on “punishing” Ethan with an action that was unrelated to the behavior (like taking away recess or talking to the principal), Ms. Jones reinforced for Ethan that he can always make a better choice in order to get the reward of sharing ideas with his community – and until he is ready to make that choice, he will not enjoy that reward.

Other things to think about when supporting positive conduct choices:

-

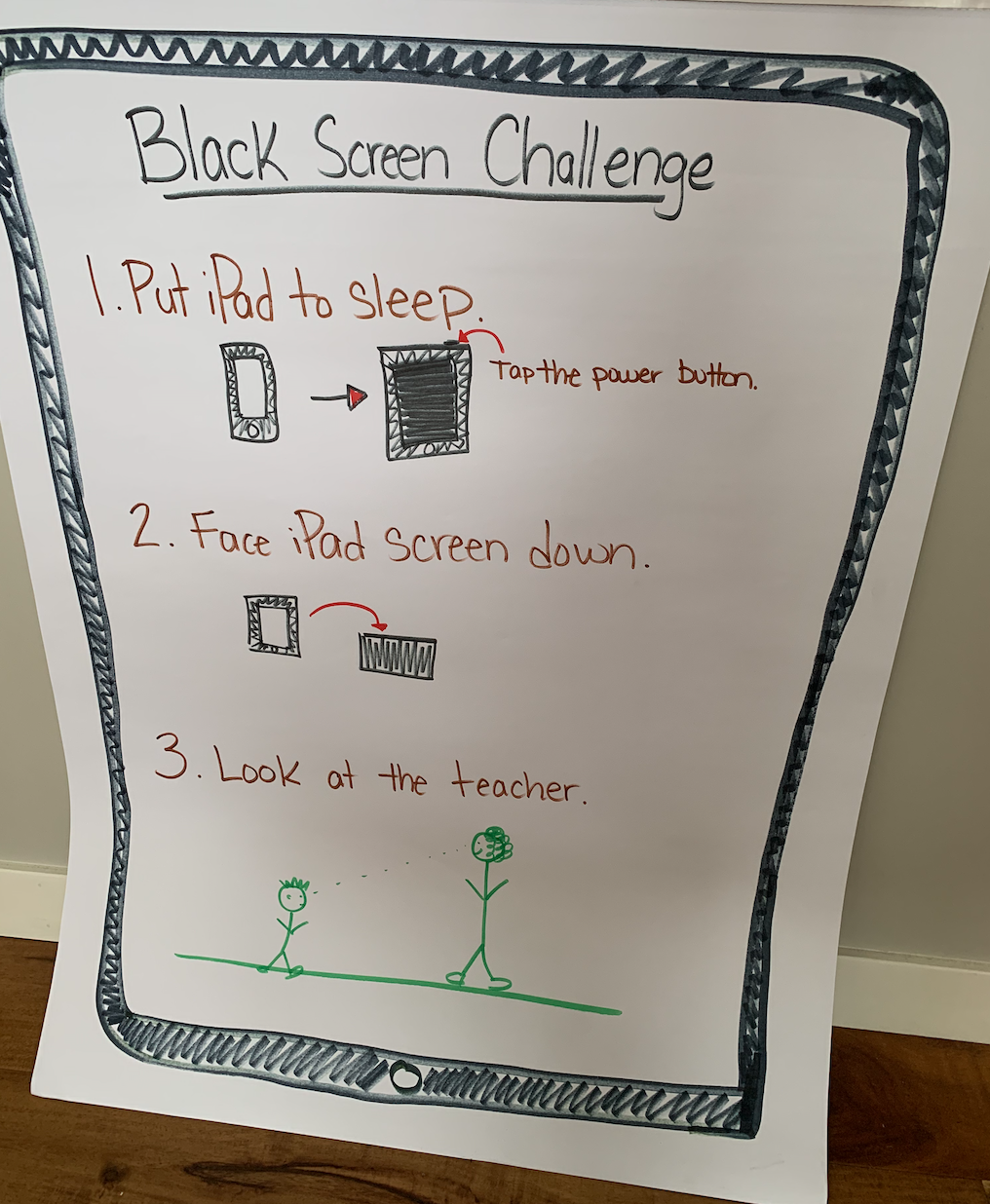

Make it more fun to choose the positive behavior. For an example of this strategy, check out Angie’s blog post on the Black screen challenge (fig 1)

-

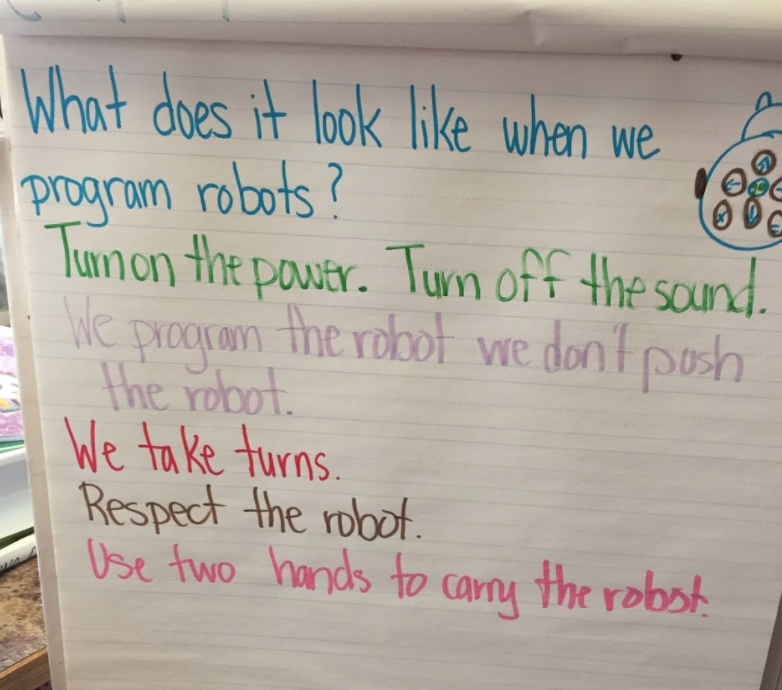

Invite children to help set the expectations for the use of the technology (fig 2)

-

Take action on the behavior, not the device. If a student is sending inappropriate messages on an iPad, consider how you would react if they were passing paper notes.

Note: We advocate for strategies to support intrinsic motivation. However, some students respond well to external motivation. If you’re planning to use tools like points (e.g. in Class Dojo), try not to use it punitively, and make the rules for earning points very clear from the beginning to avoid confusion and disengagement.

Part two of this topic will be published in March.

About the Authors

Angie Kalthoff is the Product Manager for Curriculum and Instruction at Capstone. Over her career she has been an English Language (EL) teacher, Technology Integrationist, Program Manager, and University Instructor. She has an M. Ed in Teaching and Learning. Connect with Angie on Twitter: @mrskalthoff and visit her website: bit.ly/angiekalthoff .

Angie Kalthoff is the Product Manager for Curriculum and Instruction at Capstone. Over her career she has been an English Language (EL) teacher, Technology Integrationist, Program Manager, and University Instructor. She has an M. Ed in Teaching and Learning. Connect with Angie on Twitter: @mrskalthoff and visit her website: bit.ly/angiekalthoff . Dr. Amanda Strawhacker is the Associate Director of the Early Childhood Technology (ECT) Graduate Certificate Program at Tufts University’s Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Study and Human Development. She holds a Master’s and Ph.D. in Child Study and Human Development, which she earned while designing and researching EdTech like ScratchJr and the KIBO Robot at the DevTech Research Group, and was a speaker with TEDxYouth@BeaconStreet. Connect with Amanda on Twitter: @ALStrawhacker and visit her website: amandastrawhacker.com

Dr. Amanda Strawhacker is the Associate Director of the Early Childhood Technology (ECT) Graduate Certificate Program at Tufts University’s Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Study and Human Development. She holds a Master’s and Ph.D. in Child Study and Human Development, which she earned while designing and researching EdTech like ScratchJr and the KIBO Robot at the DevTech Research Group, and was a speaker with TEDxYouth@BeaconStreet. Connect with Amanda on Twitter: @ALStrawhacker and visit her website: amandastrawhacker.com Ziva R. Hassenfeld, is the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Assistant Professor in Jewish Education at Brandeis University.In addition to her research, Ziva is a passionate educator. She has taught Hebrew Bible in a variety of settings, including at JCDS, Gann Academy, Genesis/BIMA at Brandeis, Silicon Valley Beit Midrash, Stanford Hillel, Congregation Beth Jacobs, and Congregation Emek Beracha. She is a Wexner Fellow and Davidson Scholar, Class 25.

Ziva R. Hassenfeld, is the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Assistant Professor in Jewish Education at Brandeis University.In addition to her research, Ziva is a passionate educator. She has taught Hebrew Bible in a variety of settings, including at JCDS, Gann Academy, Genesis/BIMA at Brandeis, Silicon Valley Beit Midrash, Stanford Hillel, Congregation Beth Jacobs, and Congregation Emek Beracha. She is a Wexner Fellow and Davidson Scholar, Class 25.